- Home

- Barbara Petty

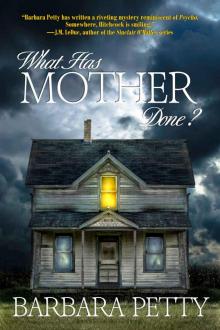

What Has Mother Done?

What Has Mother Done? Read online

WHAT HAS MOTHER DONE?

A Thea Browne Mystery

BARBARA PETTY

SUSPENSE PUBLISHING

WHAT HAS MOTHER DONE?

By

Barbara Petty

DIGITAL EDITION

* * * * *

PUBLISHED BY:

Suspense Publishing

Barbara Petty

Copyright 2015 Barbara Petty

PUBLISHING HISTORY:

Suspense Publishing, Digital Copy, March 2015

Amazon Publishing, Digital Copy, April 2015

Suspense Publishing, Digital Copy, August 2018

Cover Design: Shannon Raab

Cover Photographer: iStockphoto.com/jmbatt

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of various products referenced in this work of fiction, which have been used without permission. The publication/use of these trademarks is not authorized, associated with, or sponsored by the trademark owners.

OTHER BOOKS BY BARBARA PETTY

THRILL

BAD BLOOD: LOVE HURTS

DON’T TELL DADDY

DEDICATION

For my dear friend Grayson Cook

Who inspires me still

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At the top of this list is Sheila Lowe, brilliant writer and handwriting analyst, but for me she is also the essence of a mentor and a true friend. I am forever in her debt.

Critique group members who helped enormously in getting me over the bumpy patches are Raul Melendez, Sarah Howery Hart, Mary Moeller, and Scott Silverii. Other friends who have helped by being general cheerleaders and ass-kickers are Janet Carr, Morgan Cook, Victoria Giraud, and the one who got the ball rolling, Delores Compton.

My friends in the Thursdays are Murder book group gave me great encouragement and support: Suzanne Epstein, Martha Gruft, Laura Podell, Marilyn Borisoff, Pam Dehnke, and Suzanne Rizzolo.

I also acknowledge the tireless support of both my brother, Dr. William Petty, and my husband, Steve Mitchell. I am privileged to have these two amazing men in my life.

And, finally, I’d like to acknowledge all those who have lived with the scourge of Alzheimer’s. Either in their own lives or the lives of family members or friends. They are truly brave souls.

PRAISE FOR BARBARA PETTY

“A gripping drama unfolds as Barbara Petty explores the tensions between a woman with Alzheimer’s accused of an unspeakable crime, and her daughter, an investigative reporter determined to clear her mother’s name. Well worth the read.”

—Sheila Lowe, author of the Forensic Handwriting Mystery series

“Thea Browne returns to her small hometown to discover nothing is at it seems. Struggling with the death of her beloved stepfather and her mother’s Alzheimer’s, she becomes caught in a web of intrigue as events from the past lead to danger in the present. A must read.”

—Mike Befeler, author of “Mystery of the Dinner Playhouse” and the Paul Jacobson Geezer-lit Mystery series

“Petty builds a strong character and supporting actors in this compelling story.”

—Peg Brantley, award finalist for “The Sacrifice”

“Barbara Petty has written a riveting mystery reminiscent of Psycho. Somewhere, Hitchcock is smiling. And to think, this is just the first of the Thea Browne Mysteries.”

—J.M. LeDuc, author of the Sinclair O’Malley series

WHAT HAS MOTHER DONE?

BARBARA PETTY

CHAPTER 1

Thea Browne was trying hard not to stare at her mother. It wasn’t easy. It was like looking at one of those extreme makeovers—only in reverse. Any glance in Mother’s direction had to be taken on the sly. Her mental faculties had dwindled away, but at the same time her radar for gawking had apparently become hypersensitive. A gaze that lingered on her much more than a nanosecond would set her off. “What in hell are you lookin’ at, Miss Smarty Pants?” And then she’d throw in a half dozen or so swear words that Thea wasn’t even aware her mother knew.

Okay, the poor woman had Alzheimer’s, but when had she gotten so bad? Had this outlandish behavior and appearance been prompted by the shocking, sudden death of her husband, George Prentice?

At the thought of her stepfather, Thea’s eyes welled up. She felt his loss deeply. Her bond with him was perhaps stronger than the merely biological one she had with her mother. An image of him sprang into her mind: his eyes fighting laughter as Thea affectionately teased him about the silly, vainglorious toupee he insisted on wearing. It was a point of pride with her that she was the only person he allowed to mention the “T” word in his presence.

Had George, in his recent phone conversations with Thea, been glossing over the extent of her mother’s sad decline? Perhaps George had been able to keep her appearance somewhat more subdued and, with him now dead, Mother had run riot through her makeup case and her closet.

The woman she had been, the woman who had prided herself on her fashion sense and her good looks, had clearly disappeared down the rabbit hole of her incurable disease. And just like Alice, Thea felt as if she had stepped through the Looking Glass to find a bizarre mirror image of her mother. She had turned into a blowsy shrew who had grown too fat for her clothes and had no idea that she looked like a plumped-up bratwurst in them. Fatty rolls of skin strained the buttons of a sequined purple cardigan and rounded flesh peeked over a large rhinestone-studded safety pin which held together the zipper on her pants.

Her makeup might have been applied by a child who found the lines of the coloring book much too confining. And her hair—oh God, what had George been thinking when he’d bought her that wig? It was a flat dark-brown (her real hair was a silvery brown), had thick rows of waves and curls, and right now it was sitting askew on her head, much like a rakish hair hat. Thea longed to rip it from her head.

But that would set Mother off; wailing and whining and howls of outrage would follow. Thea’s younger sister, Beryl, had already pushed that particular button just a little while ago when she tried to wrest the remote control for the TV out of Mother’s hand.

The volume level was set so high that Thea could see glass figurines in a nearby cabinet vibrating as Mother flipped from the swelling notes of a soap opera theme to the raucous tones of a game show. It was giving Thea a headache.

No, that wasn’t true. Her headache had started somewhere over Arizona on her red-eye flight from Los Angeles to Chicago and then had settled in during the hour-and-a-half drive from O’Hare to her hometown of Rockridge.

When she’d arrived here and seen her mother’s condition, the headache had gone into overdrive. She’d lost track of the number of ibuprofen tablets she’d taken so far—six, eight?—they hadn’t helped. The headache was still there, a ribbon of pain just above her eyebrows and across her temples. She rubbed her forehead and, under the camouflaging tent of her fingers, risked a glance across the den at her mother, who was now ensconced in her dead husband George’s leather Barcalounger, the TV remote a weapon in her hand which she wielded like a lightsaber, zapping away at the images on the screen.

And then, just to add to her misery, Thea felt a hot flash coming on. Not one of those rip-off-your-clothes-and-jump-screaming-into-the-swimm

ing-pool ones. No, this one was more like, “Who turned up the heat in here?” True to its namesake, it was over in a flash. Barely worth noticing. Only a gentle reminder of the delights of menopause.

Beryl, who had taken to floating around the house, doing her best to stay out of Mother’s sightline, appeared at the door to the den in a cloud of Chanel N° 5, posing with her hand on her hip, displaying her nouveau riche finery: heavy gold bracelets, eye-popping diamond studs, black leather pants and a mourning-black cashmere turtleneck with an Hermès scarf draped over it in such a casual manner Thea knew it must have taken her sister several minutes to arrange.

“What’s up, Bear?” she started to say, but was silenced as her sibling tossed her formerly mousy brown locks that used to match Thea’s own, but which were now agleam with golden highlights. She then inclined her head ever so slightly to the left, indicating the dim figure of a man standing just behind her. Someone Thea didn’t think she recognized. But then again she couldn’t be sure. People she thought were strangers often turned out to be someone she’d known when she’d lived in Rockridge thirty-odd years before. Sometimes they’d turn out to be someone she’d known vaguely as a child or they were the relative of someone she’d gone to school with. And invariably, they knew more about her than she did about them.

Thea nodded to Beryl, letting her know that she’d gotten the message: “This is someone you need to meet.” She glanced back at Mother, who was still absorbed with whatever was on the television, and then rose and walked toward Beryl and the man.

He looked to be in his late forties. He was square-jawed and moderately attractive with sandy blond, somewhat shaggy hair and grayish-blue eyes that had world-weary bags under them. He was dressed in a brown tweed sports jacket, blue oxford shirt and a tie the color of mud.

“Thea,” Beryl was saying now, “this is Jerry Anderson. You remember Jerry’s sister, Beth, don’t you? She was on the cheerleading squad with me...”

Oh, Thea thought, you mean Beth the Bitch? She gave Beryl a knowing smile that said she remembered bottle-blonde Beth all too well, but when she turned her gaze on Jerry she forced her smile to become more polite. “Sure I remember Beth,” she said. “How’s she doing?”

He didn’t return the smile. “So-so,” he said. “She’s in real estate.”

Beryl cleared her throat. “Actually, Jerry’s here on business, Dot—er, Thea. He’s a detective in the police department now.”

That explained his brusque manner. “What do you need from us?” Thea asked. Almost certainly, this visitation had something to do with George’s fatal accident, a fall from a scenic cliff overlooking the Ridge River that ran through town. She glanced back at Mother. “Maybe we should go in the other room.”

Beryl led the way across the foyer into the living room. Sitting in the corner, Thea’s favorite relative, Aunt Dorothy, had her silver head bent toward a couple of the neighbor ladies who had come to help out with the cooking. Apparently, they had come here to have a conversation away from the loud television soundtrack.

Aunt Dorothy’s sharp hazel eyes went straight to Jerry Anderson.

“Oh!” the detective blurted out, clearly surprised. “Miss Linley!” It was yet another example of what Thea had come to think of as the “Auntie D. phenomenon”: a strong, capable adult turning into a bumbling adolescent in the presence of his former high school English teacher.

Aunt Dorothy nodded at him, but the wary look on her face revealed that she knew what he was now and that she guessed he was on an official visit. She jumped to her feet and shepherded the ladies out of the room. “I’ll go see if I can get your mother to turn that down,” she said, then sighed. “I don’t know what’s gotten into Daphne. She’s certainly not deaf.” Even in the living room the sound from the television was still obnoxious.

The detective watched as Aunt Dorothy and the two ladies exited, and Thea thought she saw him heave a sigh of relief. She pulled the pocket doors closed behind her and gestured to Jerry Anderson that he should sit, but he shook his head.

“I have something to tell you both,” he said, but instead of looking at them, his gaze wandered fitfully around the room to each of the dark, elaborate antiques as if he were looking for a safe place to land. Finally, he turned to stare out the bay window at the street beyond.

Watching his display of discomfort, Thea felt her stomach lurch; something bad was coming, she could feel it. But she willed herself to sit down primly beside her sister on the stiff horsehair sofa. Beryl had somehow managed to snake her clammy hand into hers, just as she had done when they were children and about to be punished.

Squeezing her younger sister’s hand, Thea said, “Whatever it is, I wish you’d just tell us.”

His gaze came back to them, then settled on an arrangement of white, waxy calla lilies on the coffee table in front of them. He frowned at the flowers as if they had in some way offended him. “Some evidence we found makes us wonder if your stepfather’s death was an accident,” he said.

Thea heard Beryl gasp and felt her hand go rigid in hers.

“I don’t understand,” she heard herself saying. “What does that mean?”

His eyes met hers. His were grey-blue stones. “It means that your stepfather appears to have been the victim of prior abuse.”

“Oh, my God,” Beryl uttered next to her.

“Abuse? You mean somebody beat him…” Thea felt a void cracking open inside her. “Our mother? Is that who you think?”

He nodded. “Mr. Prentice’s doctor confirmed it.” His eyes turned even harder. “Do you have any knowledge of this abuse?”

Thea dropped her gaze to her and Beryl’s hands, so tightly intertwined. “Well, uh…George told me that she would sometimes get angry and frustrated and then she’d, uh, strike out at him…but he made it sound harmless….”

“There were old bruises all over his body,” he said. “Does that sound ‘harmless’ to you?”

Thea met his implacable eyes. She shook her head without saying a word. She knew George had shielded Beryl and her from some of their mother’s worst behavior, but she still wasn’t convinced that things had been that bad.

“And that’s not all,” Anderson added, his voice an ominous monotone.

Thea glanced at Beryl, but her sister’s eyes were shut. Typical. Not wanting to face the truth. Thea looked back at him. She longed to scream, ‘What? You officious son-of-a-bitch!’ But all she said was, “What else?”

His chest heaved as he took a deep breath. “The medical examiner found additional fresh bruises—”

“Well, of course,” Thea said with some irritation. “He fell from a cliff. Naturally, there—”

He silenced her with a look. “Right. He landed on his back, but I’m not talking about those bruises.”

At that moment Thea wanted to pull a Beryl and squeeze her eyes shut and stick her fingers in her ears. But she couldn’t do that. She had to hear the truth. “What other bruises?” she asked, her voice raspy with fear.

“Bruises on his chest, two of them.” He spread his hands out in front of him, palms facing them. “Like somebody shoved him.”

There was a moment of silence, then Beryl yelled, “No!” She jerked her hand from Thea’s, jumped up from the sofa and lunged across the room, jerking open the pocket doors and banging them shut behind her as she fled.

He looked at Thea as if nothing had just happened. “Do you understand what I’m saying?” he asked.

“Of course,” she said, not disguising her indignation, “you’re telling me that you think George’s fall wasn’t an accident, that somebody pushed him, and the likeliest candidate for that is my mother, since she happened to be the only other person there. Is that right?”

He frowned. “Believe me, I’m not happy telling you this.”

“I can see that,” Thea said, trying to rein in her emotions, which right now were a confused mixture of shock, fear, and anger. “What—what do you plan to do about it? Are you going to

arrest her?”

His gaze went blank for a fleeting second, then he shook his head. “Not now,” he said, “but…”

“But what?”

“Who’s going to take care of her? Your sister?”

Thea sighed. “Not Beryl, no. She’s in the middle of a messy divorce. She can’t deal with Mother right now.” Or ever, she thought to herself.

“Then you,” he persisted. “Are you going to move back here and become her caregiver?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “My own husband died about a year and a half ago, I’ve got nothing to tie me to L.A. right now…so I guess I’m the obvious choice.”

“You might want to rethink that,” he said.

CHAPTER 2

Alone in the backyard, Thea sat perched on a low brick wall shivering against the cold. She’d grabbed an afghan from the sun porch as she’d rushed out the back door, so desperate to get away from the overheated house with its prying eyes and whispering voices that she hadn’t bothered with a coat. But now she regretted her rashness—the afghan wasn’t doing much to keep out the wind and the Northern Illinois late-March chill as the blue-gray afternoon faded into night.

She still had that god-awful headache and, for the first time in years, she craved a cigarette. It wasn’t a true physical craving—although it would give her an excuse for being out here alone—it was more the distraction she longed for, something to focus on other than the dark, insistent thoughts beating against the walls of her mind. The worst one being: Is my mother a murderer?

Thea pulled the afghan tighter, but it couldn’t keep out the cold or, more urgently, what was bothering her. Was Jerry Anderson right? Was Mother dangerous? The question of Mother being a murderer was foremost, but other questions were buzzing in her mind, too. Such as, if Mother didn’t go to a nursing home right away, was Thea up to the task of being her caregiver?

What Has Mother Done?

What Has Mother Done?